Romans (Part 09) – Judging Good and Evil (ch 2 intro)

07/10/2017 12:14To ensure we keep a solid hold on the handrails as we move along, I want to review our outline so far. (Don’t worry if you see slight changes of wording now and then. We are refining as we go.) Part 1 covered the introduction to the letter.

Romans Outline

Part 1: Introduction (1:1–17)

I. General Study Introduction

A. Who wrote the book

B. When was the book written

C. Why was the book written

II. Theme of Romans—the Gospel (1:16–17)

A. Paul is not ashamed

B. The gospel is God’s power for salvation

C. The gospel is to the Jew first and also to the Gentile

D. God’s powerful salvation reveals his righteousness

E. God’s righteousness is revealed from faith to faith

III. Letter Introduction (1:1–15)

A. Paul introduces himself

B. Paul introduces his calling—to deliver the gospel

C. Paul explains his mission—to bring about the obedience of faith

After the introduction, we moved into the first main portion of Paul’s message—to understand the common condition of humankind as being outside relationship and God’s righteousness (faithfulness to his Trinitarian covenant revolving around the three Persons’ essence of truth, goodness, and beauty) that requires God to execute judgment for good and against evil. In this first main section of the message, then, we have moved as far as shown in the outline below:

Part 2: God’s Righteousness: Judging TGB (1:18–3:20)

(Remember: TGB--used throughout the summary--stands for Truth, Goodness, and Beauty, which is the essence of God.)

I. God’s Revelation and the Effects of Turning Away (1:18–32)

A. “For” connects 1:16–17 with the rest of the book

B. God’s punishment is revealed

C. God’s attributes are revealed

D. Punishment and attributes revealed to and in us

E. Glory of God exchanged

F. God delivered them up

II. God Will Judge Good and Evil (2:1–16)

A. Understanding Paul’s Delivery

We finished with Part 2, point I, last time. There we saw the effects both of humankind turning away from God and the resultant extrapolation of the horrific consequences as God turns away (or gives up his relational care for us). I want to spend a few moments longer ensuring we understand Paul’s trajectory before we get there. Remember that there are as many commentaries on Romans as there are songs about love. Actually I don’t know how many love songs there are, but my point is to stress the astounding number of differing opinions and conclusions scholars have drawn from these sixteen chapters of Romans. No one writes a commentary because he or she wants to say the same things as have already been said. So the huge number of commentaries tells us that there are a huge number of beliefs about what Paul meant that differ from each other. And therefore it isn’t helpful for us to skim along at the beginning where subtle divergent presumptions wind up with wildly varying angled results. We need to match our approach as much as possible to Paul’s presumptions as he begins to write.

I’ve called part 2 “God’s Righteousness: Judging Truth, Goodness, and Beauty” for a specific reason. I believe that in Paul’s explanation of gospel, he is making distinct initial points to which we may think all students of biblical truth agree, but they do so only in a general way rather than in subtle point. In chapter 2 we find Paul drawing a very hard line in arguing that God judges between good and evil. Yes, Paul wants his actual audience (the Roman Christians) to understand their failures. But we can’t simply focus only on humankind in this discussion; Paul is making a point about God. How should we understand God in this point Paul is making? Why is God consumed with judging good and evil? What does this mean in regard to his mercy? Will his mercy stand opposed to his judgment against evil? Must God eventually have to choose between his own love of TGB and his mercy for failing humankind? Are justice and love truly at odds? Well, all that is still to come. But we can’t understand those conclusions Paul is eventually going to draw if we don’t understand from the beginning how important TGB is to God and why he is drawing a hard line in the sand between good and evil.

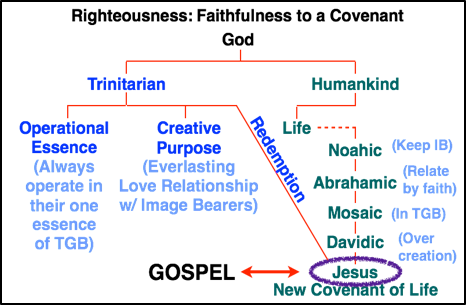

Let’s go back for a moment to the explanation for righteousness. We introduced some of the multi-faceted complexities of the concept in Summary 2 of this series, and we explained a little more in Summaries 3 and 5. To complete our view, let’s rehearse what we know.

First, the plain and simple definition for righteousness is faithfulness to a covenant. That’s it. Whether we are talking about an agreement made with some other person, the responsibilities of a judge, the responsibility of God in making all things right, or whatever situation involving any party with agreed-to obligations, the faithful keeping of those covenant obligations is termed righteousness. Both the Greek and Hebrew roots of the word have to do with standing or status, and thus being found standing rightly in regard to your covenant obligations is being faithful to the covenant—being righteous.

Most of the covenants we run into in the Bible (at least the major ones) are those in which God is one of the parties and humankind in some way makes up the other party. But alluded to in the Bible are a couple of covenants in which God either makes promises to himself or operates based on who he is—which essentially is a covenant in himself. I refer to this kind of covenant as a Trinitarian covenant. For example, God will always operate according to his own essence of truth, goodness, and beauty. We cannot even imagine, for example, God the Father operating in a manner outside TGB. The Holy Spirit would not do so either. And, of course, neither would the second Person of the Trinity. From Jesus’s claim in John 14 of being the Way, the Truth, and the Life to Romans 8:28’s insistence on all things working for good, we know God in his Persons always operates by intent in truth, goodness, and beauty. If any of the Persons did not, that Trinitarian covenant would be broken. God would essentially cease to be God (an unthinkable, incomprehensible, impossible theoretical concept). So then God has this Covenant of Operational Essence in which he, in his Persons, will always act according to his TGB essence.

Another of God’s Trinitarian covenants is his agreement to create image bearers for everlasting love relationship—his Covenant of Creative Purpose. That promise is all through the Bible, but probably best summarized in Titus 1:1–2. That was a covenant made by God before the world ever was made. Now, these two Trinitarian covenants appear to be fine, well, and good, and indeed they are. But a huge wrinkle was creased when Adam and Eve ate that apple. Instead of the Trinitarian covenants working in conjunction, with the entrance of sin in creation, they became actually pitted against one another. On the one hand, God had to maintain his righteousness in operating in TGB; in other words, he had to judge and separate from sin. But on the other hand, if God eternally separated from his creation (essentially annihilated them), he would be unfaithful (unrighteous) in his Trinitarian Covenant of Creative Purpose--to create for everlasting love relationship with those image bearers.

God of course knew beforehand of this problem that would occur. He therefore made a third Trinitarian covenant in which he (they—the Persons of the Trinity) would redeem this creation, including the human image bearers. Notice that this Covenant of Redemption—although a loving act for the creative purpose of love—has the added dimension of being necessary to maintain God’s righteousness balancing his two other Trinitarian covenants.

Now, in the Covenant of Redemption, God initiates several other covenants--not Trinitarian, but with humankind--to picture and guide what he is doing overall in the balance of his Trinitarian Covenants of Operational Essence and Creative Purpose.

God initiates four covenants with humankind: the Noahic Covenant, the Abrahamic Covenant, the Mosaic Covenant, and the Davidic Covenant. The Noahic Covenant showed that God would be true to his Trinitarian Covenant of Creative Purpose by not totally destroying creation because of their sin. The Abrahamic Covenant emphasized the relationship God was establishing with his image bearers to be of faith rather than force or coercion—essentially a relationship of love (again according to his Covenant of Creative Purpose). The Mosaic Covenant, however, proclaimed emphatically that the relationship could be possible only in fulfillment of the pure TGB requirement for activity. Sin was not tolerated, and the Mosaic Covenant, then, became something to show humankind their inability in this regard. Finally, the Davidic Covenant spoke of rule and reign—that which God’s image bearers were created to do, which is pictured in David’s reign over God’s Promised Land.

Of course, the perfect righteous fulfillment of these four covenants with humankind could not be accomplished by any human born of Adam. God, in his Trinitarian Covenant of Redemption, decided himself to take on human flesh as Jesus to succeed where Adam’s humans failed. Thus, Jesus, the man, fulfills the human covenants and then through his unjustified death and justified resurrection provides a way for humankind to be reborn into him and into relationship with God.

This process I just recounted is what has Paul so excited. This is the gospel! This is the good news! Remember, Paul didn’t say the gospel was salvation (in 1:16). Paul said the gospel was the power for salvation. The gospel revealed God’s righteousness (1:17) in his faithful accomplishment of all three of his Trinitarian Covenants! God is making all things right through Jesus, the human covenant keeper, who in his death and resurrection became the Lord of all this redeemed creation! Through all his work with this creation, God is shown to be righteous! Jesus is Lord! This is the gospel!

Here is a chart depicting our discussion on righteousness. Read through this section again with the chart as a picture guide.

Moving on, then, in our study, we find that Paul showed in chapter 1 that humankind broke covenant (broke relationship) with God. Paul is about to show in chapter 2 that all humankind, then, must be judged by God who, based on his Trinitarian Covenant of Operational Essence, must judge between good and evil. Don’t get ahead of Paul telling the story. Yes, we can see in the chart that there are other covenants culminating in redemption. But Paul hasn’t gotten there yet. Chapter 2 is way back at the beginning, and at this point, Paul is discussing sinful humankind simply in relation to God’s Covenant of Operational Essence. And the conclusion from that is that God must judge.

One more thing is necessary before we get into the discussion of chapter 2. Paul engages in a rhetorical style called diatribe. That term is not supposed to carry today’s meaning of abusive speech in satire or other criticism. The traditional meaning of this rhetorical device reflects a writer engaged in debate with one or more imaginary opponents, asking rhetorical questions and answering any objections that the writer imagines they may bring up. What that means for us is that Paul has an actual audience—the Roman Christians to whom he is writing—and an imaginary audience—non-Christians with whom he engages in debate. We can even break down this imaginary audience into two groups: non-Christian Gentiles who cling moralistically to philosophies of the world and traditional but non-Christian Jews who moralistically condemn all who do not cling to the Law (i.e., the Law of the Mosaic Covenant). Both these non-Christian subset debate opponents of his imaginary audience still have a tendency to judge others. After all, though unsaved, they were made as image bearers, holding a conscious morality by which they understand good and bad. And these people have no problem accusing others, based on their own judgments, of being in the wrong and deserving of punishment. And that is why Paul begins chapter 2 as he does. He says to these non-Christian morality judgers, “Therefore, any one of you who judges is without excuse!”

We have heard Paul talk about being without excuse earlier. After explaining that God has revealed his divine attributes (TGB), his eternal power (loving care), and wrath on unrighteousness, Paul stated that because of that tri-fold revelation, people are without excuse (1:20b) when they fail to worship him (glorify and show gratitude—1:21a). And then Paul explained the detail of God giving them over to their own cravings, breaking down the image of relationship with God (1:26–27) and relationship with each other (1:28–32). In essence then, Paul declared all humankind to be sinners. If all humans are sinners, any of those sinful humans who stands up to say another human is guilty of sin and deserves punishment is in essence saying they themselves too should be judged guilty and deserving of punishment.

Paul then describes those people (of his imaginary audience) who will judge others but think themselves okay as despising God’s mercy. The Greek word kataphroneo translated here as despise, means not placing value on something—considering it worthless. For example, people had a tendency to think little of children, but Jesus warned that we must become as children to be part of the Kingdom of Heaven (Mt 18:3). He then said that they therefore should not “despise” or kataphroneo or consider worthless those little ones (Mt. 18:10).

The idea here is that God is merciful in giving us sinners the gift of time to repent. When we think ourselves not needing to repent and spend our time judging other sinners, we show that we think the mercy God has given us is worthless—we, as Paul says, despise it.

Notice too that it is this kind of person who is described as having hardness and an unrepentant heart. Normally, as we think of hard, unrepentant people, we may imagine them to be scowling against God. But that is not the picture here. These people are those who believe in moral goodness and who think themselves on the side of good, without recognizing their sin because they have shrouded over the source of goodness—the one true God.

—————